I gave this talk at Responsive Day Out on June 19th in Brighton. It was a 20 minute talk. Normally I aim for 1 hour of prep per minute of speaking. Russell reckons that’s the a good rule of thumb for writing a new talk anyways, and he’s really really good at them. This talk took a lot longer than 20 hours to write. It was probably more like 35 by the end.

I started off thinking this talk would be me standing up and presenting the business case or cases for accessibility. But by the end of the first 20 hours of writing and rehearsing, what I had was a talk full of conjecture, mostly me going: “maybe this is a business case if all these flimsy and unlikely things apply to you…?!?” So with a week to spare I re-wrote the talk, and then I re-wrote it again.

The audio of the final thing is available at http://responsiveconf.com.s3.amazonaws.com/2015/audio/01-alice-bartlett-responsiveconf2015.mp3, and I’ve dutifully uploaded my slides to speaker deck. Here is a write-up-ish of what I said in Brighton.

“What is the business case for Accessibility?”

I’m giving this talk because I keep hearing people ask that question. Having never really thought about it, I’d always assumed there must be a business case and when people have asked me what it is I’ve just made something up. I’m motivated by the moral case. The one that goes:

At the present time I’m sitting on a great pile of privilege and there isn’t anything I can do to change the amount of privilege I have. But I can use that privilege to help other people out and I should try to increase equality of opportunity wherever I can.

So as a front-end developer making my sites accessible feels like the least I can do.

Which means I’d never given the business case much consideration. Some people are better motivated by money, and indeed some people will say:

If my business doesn’t make money then how much it furthers equality of opportunity will be moot because my company won’t exist.

And that seems like a valid concern.

What is GOV.UK?

Hopefully you all know this so I’ll keep it short. GOV.UK is the best place to find government services and information. We have things like “when is the next bank holiday?”, “what is the current travel advice for Egypt?” and then a lot of more obscure stuff like “What is the import tax ruling for a human skull shaped plastic object that contains LEDs embedded in the eye sockets?” (It’s classified under: ‘CN code 3926 40 00 as other ornamental articles of plastics’).

We’re the 30th most popular site in the UK; that’s more popular than Tumblr. We’re home to 330 departments and organisations. We’ve tried to make GOV.UK as accessible as possible but it hasn’t always been this way.

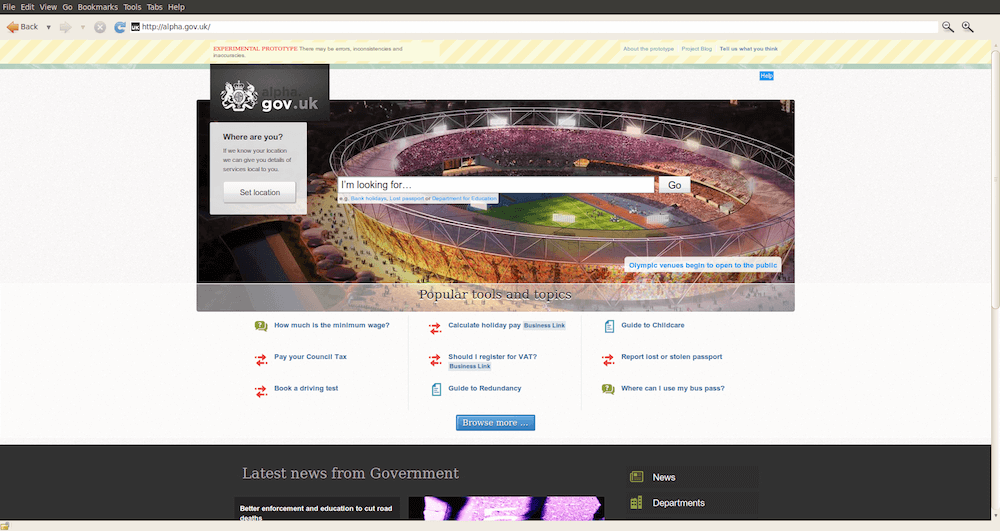

The GOV.UK alpha was not accessible and we got a kicking for it. (This was before my time, but I’ll keep saying “we” because it’s a difficult habit to break…) When we launched the alpha it was a tool to provoke change and make a point within government but the decision to avoid accessibility sent out a bad message to many early users.

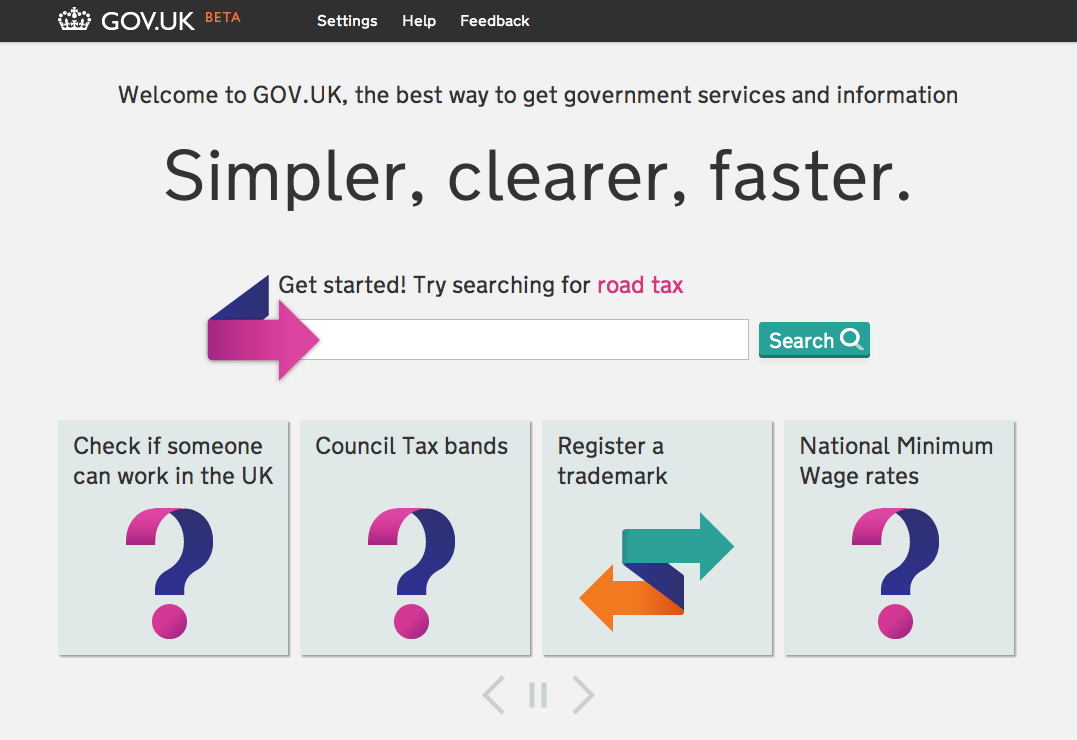

In the beta we built for inclusion.

Tom Loosemore said this:

We want to make the most easy to use, accessible government website there has ever been.

And so building for inclusion became part of how we worked. We do stuff like regular testing with people with a broad spectrum of abilities, screen reader training for front-end developers and anyone else who fancies it, and we put “Building for inclusion” in our design principles:

Accessible design is good design. We should build a product that’s as inclusive, legible and readable as possible. If we have to sacrifice elegance; so be it.

What is Accessibility?

In this part of the talk I paraphrase Anne Gibson’s excellent piece on A List Apart about accessibility, but since this is the internet I can just put that link there and wait for you while you read it because it’s ace.

So, what is the business case for accessibility?

OK, this is the meat of this presentation, the good bit. Or at least it would be. I started off thinking this would be the bit where I was able to say:

Here is your magic answer to why making your site accessible would make you filthy rich.

That was naïve.

Let’s find out why. A good business case should take a problem your business definitely has and solve it in the most cost effective way possible. It should go something like this:

- You have a problem. you need more money, you need more ad impressions, your site is slow to maintain, you want people to think of us favourably, etc.

- You explore some possible solutions. Your exploration includes the cost associated with each solution, and the likely return on investment, all of which is based on evidence.

- You pick the most cost effective solution.

So if you’re writing a business case for accessibility, the business case concludes:

We should solve X by improving the accessibility of our site.

We should solve X

Now, anecdotally, there are loads of possible X’s to slot in here: We need to improve our search ranking! We need to lower our maintenance costs! We’re missing out on revenue from people with disabilities! We need to improve our image! etc.

But when you start trying to write an actual business case things get a bit trickier. Because there isn’t a whole lot of evidence that improving your accessibility is the most cost effective way to solve any of these problems.

Take “better SEO” for example. The most cost effective way to improve the SEO of your site is probably to target things that make the SEO better. Headings, text alternatives to visual content, using key words, getting a bunch of people to link to your site. A likely side effect of some SEO improvements is that the accessibility of your site will also improve, but that’s not the same as having a business case for accessibility. And the case motivated by improving SEO doesn’t get you to adding proper ARIA tagging to your components, or testing with non-visual users, or making your site fully keyboard navigable.

Let’s take another example. You want to target users with accessibility needs to get them to buy things from your site. Firstly, even before you get to cost effective solutions, just proving there is a slice of users you’re missing out on is tricky. Karl Groves has written a pretty comprehensive article on why it’s difficult to track users with disabilities across a site. There are also very few data-points for the percentage of the population that has a disability that stops them from using the internet easily. But let’s say you can establish there is a significant slice of the population that can’t currently use your site and it would be financially beneficial for them to be able to. Improving your site’s accessibility might be a way to get those users in, but maybe a more cost effective way might be to do a big marketing push on being accessible, and then fix issues when they arise. It depends how accessible your site is to begin with.

If you want to see a more in-depth dissection of the commonly thrown around business cases for accessibility, Karl Groves has done a very thorough job on his blog.

The law

There is one well evidenced business case for accessibility. It’s not getting sued. In the UK we have the Equality Act (2010) which states that service providers (that’s websites in this case) should make “reasonable adjustments” to their sites. A further clarification issued by the Equality and Human Rights commission in 2011 stated:

…the duty goes beyond simply avoiding discrimination. It requires service providers to anticipate the needs of potential disabled customers for reasonable adjustments.

The RNIB has a handy explainer for the UK law and how it affects websites.

The first ever lawsuit involving a website being sued for not being accessible was SOCOG vs Maguire in 2000. The Sydney Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (SOCOG) was sued by Lindsay Maguire for not making its website accessible.

SOCOG claimed that they did not discriminate against Mr Maguire but, if they did, fixing their site would constitute “unjustifiable hardship”.

SOCOG were eventually found to have engaged in unlawful discrimination in violation of the Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act (1992) and ordered to fix their site.

More recently, in 2006, Target.com was sued in a class action suit brought by the National Federation for the Blind, which they settled for $6 million.

In 2013 Netflix was sued by the National Association of the Deaf for not having closed captioning on its movies. Netflix had to pay $755,000 in legal fees to the NAD’s lawyers and committed to 100% captioning by 2014.

In the UK a legal case has never been brought to court, but the RNIB has threatened legal action against a number of un-named companies, who then fixed their site before the case reached a courtroom.

The litigation angle only works if the likelihood of getting sued outweighs the cost of making your site accessible. If you’re a high profile company that risk is pretty high too, so you should definitely make your site accessible.

But if you’re tiddly the likelihood of getting sued is smaller and I can’t find a business case for the small companies. I can find many positive traits associated with accessibility but I can’t draw a well evidenced line from “accessible website” to “more money”. If ROI is what you’re motivated by you might as well just make your whole website out of JPEGS and take a nap.

You don’t need a business case

BUT

If you’re building your website from scratch right now why wouldn’t you make it accessible. Building accessible websites has never been easier! Make it part of what your definition of “good” is. As a front-end developer, add it to the list of ways you know you did your job well. Sneak accessibility in if you have to.

Karl Groves (again) sums up this approach in his post how expensive is web accessibility?:

When [accessibility] becomes part of how you do things, of course it is free.

On GOV.UK building for inclusion is how we work.

We share and discuss the accessibility of design patterns on a publicly accessible hack-pad: https://designpatterns.hackpad.com.

We make small fixes to the accessibility of our site regularly. Here’s one about improving the presentation of search results using ARIA-live.

Here’s another small improvement made by my colleague @edds to tighten up the home page presentation for screen readers. This change was a tiny improvement Edds noticed because he was using a screen reader to navigate GOV.UK because that’s just part of how he works.

Start today

Start building for inclusion today: try and use your site with just a keyboard, or have a listen to it with a screen reader. When accessibility becomes part of how you work it will be free, and you won’t need a business case.